Four Corners, Four Mountains, One Homeland

I first published an essay in 1990 about choosing my four personal sacred mountains. I've since rewritten the piece for a variety of publications, each time discovering new insights. Most recently, I made a new connection that warrants yet another rewrite. Now I see that those four sacred mountains stand at the Four Corners of my world.

Here's the piece—originally called “The Sacred Mountains of Home”—in its latest incarnation.

The bullseye of “Four Corners” falls within the Colorado Plateau, the vast redrock heart-shape at the center of the West. This decisive crisscross—the arbitrary result of using lines of longitude and latitude, meridians and parallels, to define place—also happens to be the fulcrum of my experience, the epicenter of my home landscape.

I’ve lived in the Four Corners states all my life.

Straddling four states at the Four Corners Monument, 1962. I was twelve. Note the cool rabbit’s foot keychain dangling from my belt.

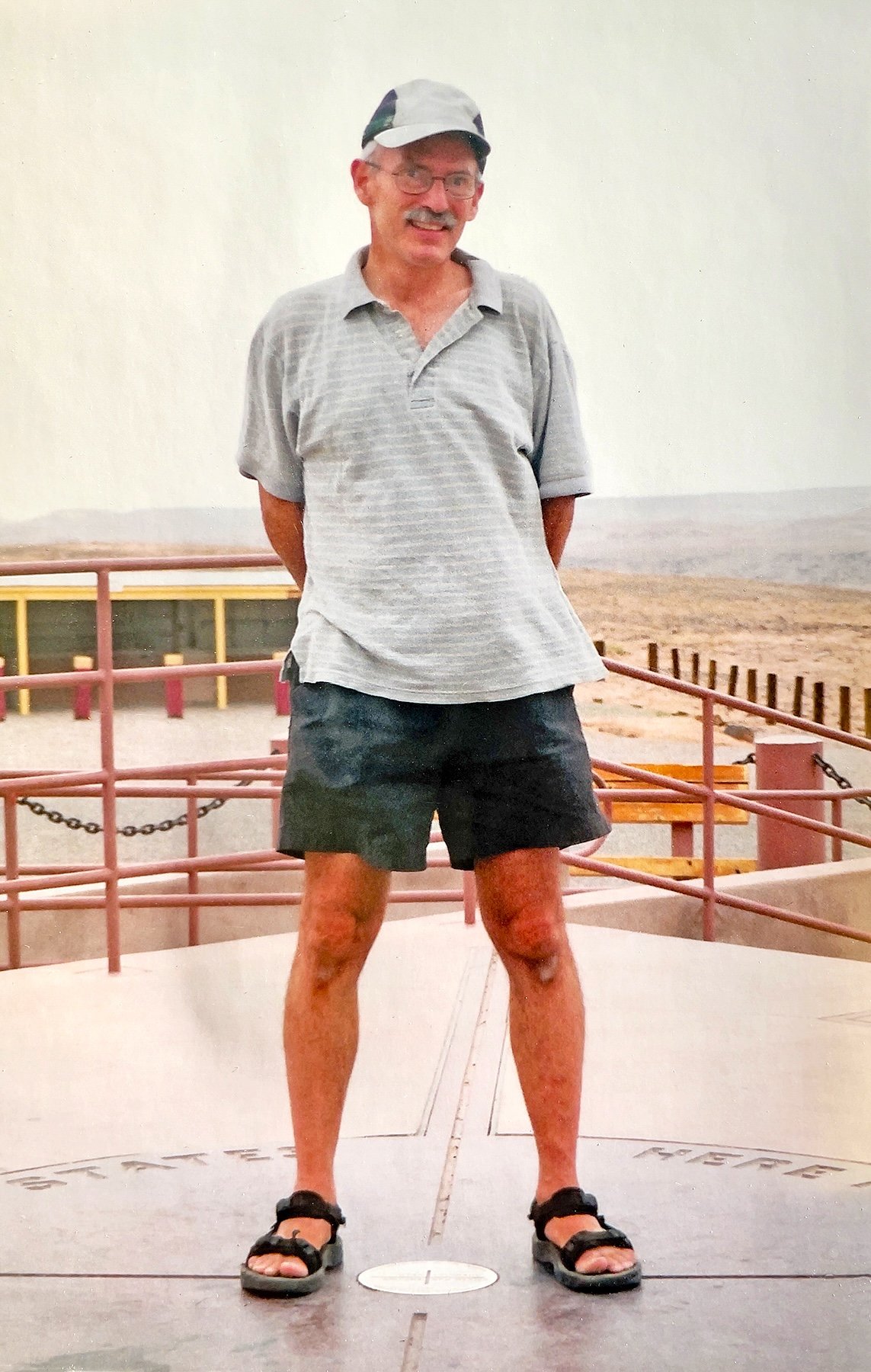

And here I am at Four Corners in 2002—a picture taken by our son, Jake, when he was 12. (Alas, I no longer have my lucky rabbit’s foot.)

National and territorial history created this cartographic anomaly 160 years ago, the only spot in the nation where four states meet. And the jurisdictions meeting at Four Corners aren’t just four states but two sovereign Native nations, as well—the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation in Colorado and the Navajo Nation in the other three quadrants.

I stand at the Four Corners monument, and I can sense the landscapes of each state sweeping away from me. I turn to the north and picture the looming Rockies beyond the canyons and mesas of Colorado and Utah. I circle to the east, and I know that halfway across New Mexico the Rio Grande slices the state in half, the great river flowing toward Mexico and into the Chihuahuan Desert. I keep rotating, toward the Arizona deserts to the south, and then to the west, where I travel in my mind’s eye through Utah to the Great Basin.

Four Corners is a perch, an intersection. From this still point, sight lines lead outward—but also inward. Imagine all these reeling-away landscapes reversing direction and convening and concentrating their energies here in this one spot. All the spiritual energy of the wildlands and human inhabitance/inheritance of the West pouring into a single point on the map. In this way, the Four Corners resembles a Pueblo place of emergence, a sipapu, and a point of convergence, too—an energy vortex like those revered by New Agers on pilgrimages to Sedona or Mount Shasta.

From here, I feel the breadth of my home landscape.

Like many Westerners, I have moved from place to place, and my sense of home has grown to include a major expanse of the West. But I need reference points, boundaries. And so I have embraced the Indigenous concept of mountains bounding sacred home ground. It’s presumptuous and perhaps inappropriate for a non-Native, but to me it is humbling and nourishing to make this bow of respect toward my homeland. It’s one way to comprehend just where I live on the surface of the earth.

As a writer, I spent a decade in my thirties and forties listening to Southwest Native people, interviewing everyone from high school students to elders. Over and over, I heard them speak of land as sacred and mountains as holy places.

Navajo people, the Diné, traditionally define their home within the boundaries of four sacred mountains, one at each of the four cardinal directions. Within this rough circle of land lies everything good, everything needed to live well. Many Native people speak of the mountains overlooking their homes with reverence, affection, and awe.

I admire this gesture of paying attention to the land. For mountain peaks give us a focus in a land where the sky and prairie, plateau and desert are daunting in scale. Mountains break up the awesome western space; they form the walls of the rooms—the lowlands—where people live and highways and railways pass through.

Most anywhere in the West, we do not live in the mountains, we live at their feet—in cities, towns, and ranches built in dry places dependent on mountain watersheds. Without water, people move on.

From these outposts we look across long horizons to where the moon and sun break over the rim of the earth, past silhouettes of nearby peaks. The proverbial “comforts of home” begin to include the landscape surrounding our warm houses—a panorama distinguished by landmark peaks.

We learn the names of the mountains. And as we acknowledge the long tenancy of Native people, we learn, too, of each tribe’s anchoring landmarks. Western Apache people told anthropologist Keith Basso that “wisdom sits in places.” Without aspiring to wisdom, I believe our lives grow richer when we pay attention to place, when we link our lives to landscape and allow mountains to help define our home.

I grew up in Denver, keeping an eye out for the horizon line of the Front Range, smoke-blue in summer, ice-white in winter. Longs Peak, with its blocky summit, was the highpoint of Rocky Mountain National Park and the northernmost “fourteener” I could see. My father loved to join me in watching for its distinctive silhouette; we picnicked at alpine lakes below the peak. Later, in college I attempted a winter ascent with my buddies and, still later, even wrote a book about the mountain. But mostly Longs Peak feels like family—a cherished backdrop that’s been with me since childhood.

Longs Peak—centerpiece of Rocky Mountain National Park, and the hovering presence on the western horizon of my childhood.

After college, I lived in Tucson for a time, watching the moon set in a pastel pre-dawn sky beyond Baboquivari Peak, the great blunt stub off to the southwest, central to the creation narrative of the Tohono O’odham people who looked up to its summit each day. Baboquivari—wild chiles growing in its canyons, caracaras wheeling over its saguaros—stood for me as a marker, a symbol of the power and soothing warmth of the desert.

As I fly into Tucson, I spot the silhouette of Baboquivari, marker of home.

From Tucson, I moved to northern Arizona, to Flagstaff, and lived in the protective shadow of the San Francisco Peaks. A Navajo man, Steve Darden, spoke to me about these peaks, sacred to his people:

"That mountain has life. That mountain has a spirit. That mountain has a holiness.

“The Holy People live there. Because of that, it's a place where I can find refuge, rebirth. I garner strength from this mountain—spiritually, from this place."

I think of the Peaks from a distance, watching clouds build in summer monsoon season over the elegant angles of their dignified summits. I see the Hopi villages perched on mesas jutting like ship’s prows over the arid plateau country that climbs from bare sandstone and twisting junipers to the one snow-covered landmark in sight, the graceful curve of the San Francisco Peaks.

These 12,000-foot summits stand as beacon and promise. They reassure us with their life and lush fertility in a region known more for naked canyons and unnerving glimpses into geologic time.

They are the most hallowed mountains in the Southwest. Everything falls away from their summits. They stand at the center of the universe.

The unmistakable silhouette of the San Francisco Peaks. The entire Southwest rotates around this summit, holiest mountains in the Southwest.

With a move to New Mexico in the 1980s, I lived in a Pueblo landscape. My house in the Rio Grande Valley lay on the axis between Tsikomo at the summit of the Jemez Mountains, and Truchas Peak along the crest of the Sangre de Cristo Range. Pueblo people still make pilgrimages to shrines atop these peaks, leaving offerings of cornmeal, prayer feathers, bits of bone and broken pottery.

I liked walking outside in the mornings to look up to the mountains and say their names: “Tsikomo. Truchas. Tsikomo.”

Truchas, with a gaping cirque on its face, rises to 13,102 feet, the second highest mountain in New Mexico. Tsikomo, a rounded dome on the rim of the Jemez caldera, has a distinctive meadow just below its peak, the only treeless patch on the western horizon.

“Tsikomo.”

Truchas Peak and the Sangre de Cristos, from my home in the Pojoaque Valley.

Now, in Salt Lake City, I live beneath the Wasatch Front. Just over the shoulder of the first rise of peaks stands Mount Timpanogos, the dominant mountain of the Wasatch Range. Massive and commanding, Timpanogos stands on Ute and Shoshone land. I can feel it out there now.

Few mountains have the grace of Mount Timpanogos.

Longs Peak, Truchas, Baboquivari, Timpanogos. I’ve chosen these mountains. Between them stretches my home. In the center place of this land stand the San Francisco Peaks, consecrated to all who dwell nearby.

As I traverse this territory, I note the mountain ranges, anticipating the next landmark coming up from beneath the horizon. The roll of the hills takes me through the litany of life zones, up from desert grassland through piñon-juniper woodland and into fragrant ponderosa pines standing still and friendly in the sun. Or down through the concentric circles of desert shrubs—sagebrush, saltbush, greasewood, creosote—toward the austere playas that form the power spots, the chakras, of Basin and Range country.

Indigenous people root their spirituality in landscape. Laguna Pueblo scholar Paula Gunn Allen says, simply, “We are the land.” Over and over, Southwest Native people have told me that the crux of their lives is simple: acknowledgment is the key, paying attention to the Earth and giving thanks for its blessings. To live with reciprocity, to listen to the Earth, we need only relax and open our senses.

Those of us not steeped in these relationships need to work a bit to tap into this healing power of the earth. To sense the land, to feel the earth stretching away from you, rising to the mountains, means paying attention. It happens incrementally, step by step. Four Corners, Four States, Four Mountains, One Homeland.