Saying What Needs to Be Said

Fifty-eight years ago this summer, my brother Mike was declared mentally incompetent and committed to the Colorado State Hospital.

I was six when Mike left home in 1957; he was 14. Diagnosed sequentially as retarded, schizophrenic, and epileptic, Mike spent ten years in the hospital before his release to halfway houses — a transfer the hospital called a “parole.” He was sent back into the world carrying the stigma of institutionalization and mental illness that’s as damning as prison time. Mike lived for another ten years, but I never spoke to him again.

Here is the letter I wish I had could have slipped into Mike’s bags when he left home, a letter he could have pulled out to read any time during the 20 years he lived without family. I couldn’t write it then. I can, now.

Dear Mike:

I was a kid when you left. I was an unsure 16-year-old when you came home to Denver when the state hospital mainstreamed you.

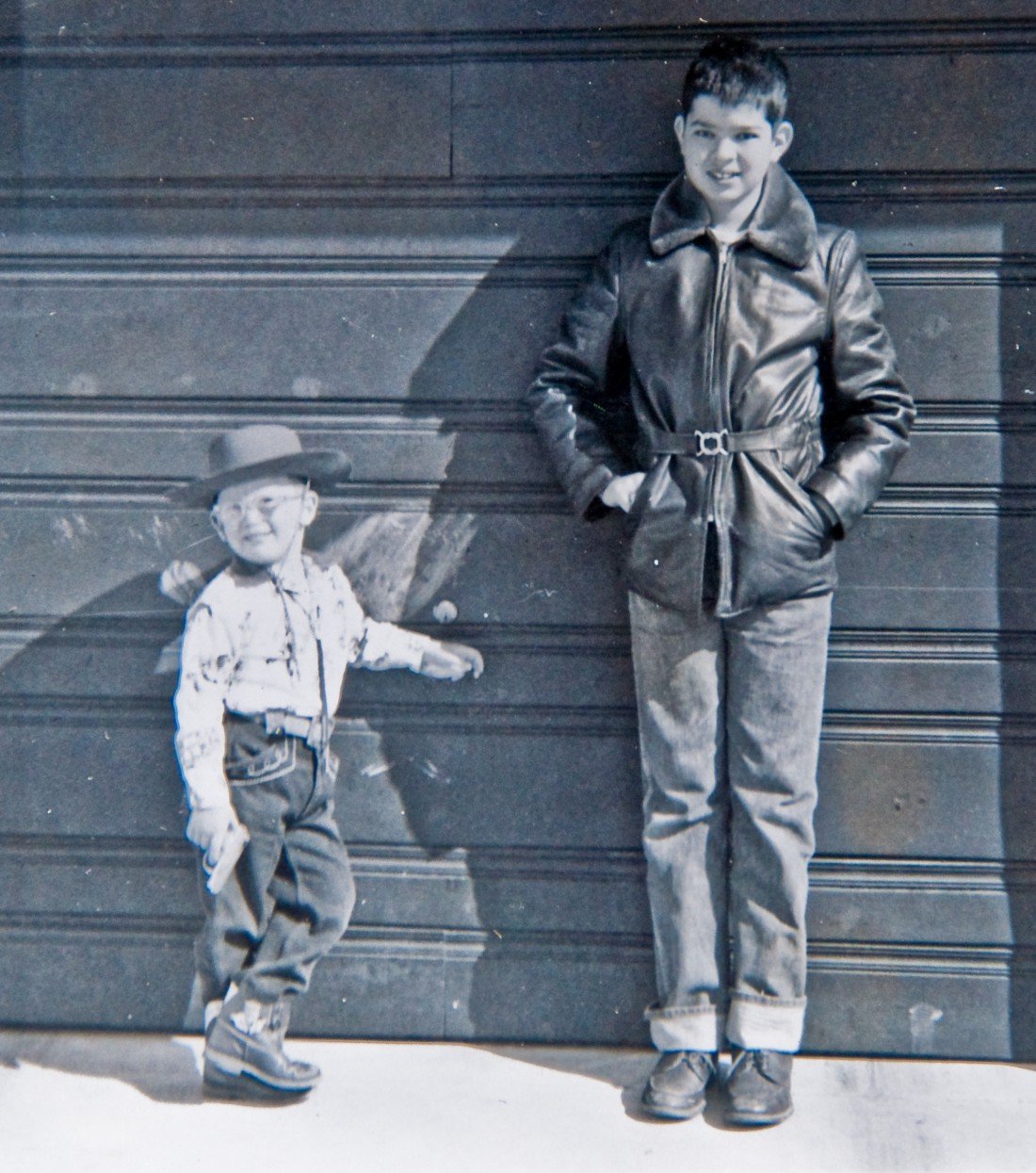

Stevie wearing his cowboy duds, at 4 ½; Mike, at 12. Denver, 1955.

And then you disappeared from my life.

The docs called you “paranoid schizophrenic, capable of violence.” I didn’t know what those words meant when I was six, but you scared me with your anger. You screamed at Mom, caging her against the wall with your arms, and I didn’t know what to do. So I hid in the garage.

I kept hiding after you left. I buried my fears. I believed Mom and Dad when they told me you were in the best place for you, and that you understood that you needed to be there. Now, I understand how you must have hated Mom and Dad for turning you over to The System, how you must have missed home.

You weren’t paranoid all the time. I know you had many times when you felt pretty normal. I’ll bet that you were thinking, judging, dreaming, yearning — even while you knew that Mom and Dad and the doctors all had separated you, isolated you, banished you, diminished you.

I didn’t have the agency or the empathy to pursue you when I could. I regret not reaching out to you. I miss having a brother in my life.

So here’s what I want to say. Even when you were gone, even when you felt desperately alone, even when you rejected us, you were contributing to our family in ways you didn’t know. Here’s what you taught each of us.

Your life taught Dad compassion. For you. For Mom.

Your life challenged Mom to define the meaning of love. She never stopped rethinking her decision to commit you — and mourning what happened to you. She didn’t hide in the garage; she was braver than I was. But she spent night after night pacing our little house, crying for your loss — and hers. I only saw her consumed by this pacing after you died; for years, she grieved alone. She didn’t want anyone to witness her sadness, to watch her lose control.

Your absence filled Mom with sorrow, but she couldn’t cope with you. She and Dad wanted only to help you, and in those days, the state hospital offered the only help they could find. No matter how guilty she felt, she knew that sending you away was her only choice.

In those years before you left, we were brothers. I was your sidekick. Playing with you made me happy; listening to rock and roll records with you added joy to my life. As a child, you gave me the gift of growing up while loving a big brother.

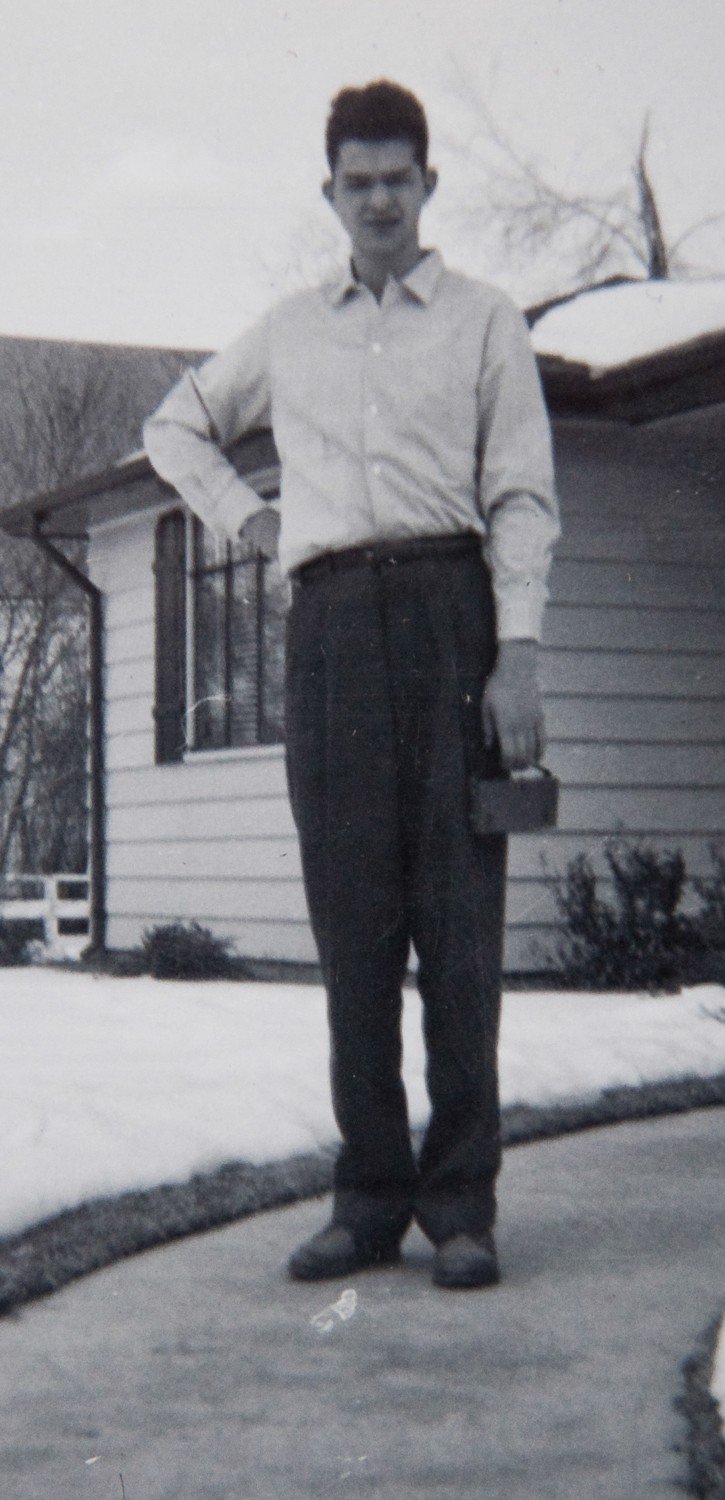

The last picture I have of Mike — a 17–year-old totem pole in the front yard of our Denver home. 1960.

Your life shaped me, made me unconsciously choose to be better, easier, more loving with Mom and Dad because I was acting for both of us, filling the role of resident son that you couldn’t fill. I had to be both sons.

All these years later, after you and Mom and Dad have died, I’ve finally come out of the garage. I’m looking back. I’m looking for you. I’m reconstructing your life. I want to make sure you have your place in the family chronicle.

Mom and Dad sheltered me from the trauma of your story, and I aligned myself completely with them. I didn’t allow myself any independent thoughts or feelings about you. Now I see that I could have built a separate relationship with you.

You told Mom to “leave you alone forever.” You never said that to me.

On this anniversary of your leaving, I want to tell you that I wasn’t mature enough to have acted on my own — to have truly been your brother.

I remember you. I love you. I miss you.

Your brother, Steve

Stephen Trimble will post stories on Medium as he works on his memoir, Leave Me Alone Forever: My Brother’s Madness, My Mother’s Sorrow. These stories give readers a preview of the book — and yield crucial new insights for Steve. Steve’s website is: www.stephentrimble.net.